Karava of Sri Lanka

Marriage

Karava Marriage customs

When girls and boys are of marriageable age the parents seek out suitable partners. The traditional requirements to be matched are caste, religion, social status, ancestry, the compatibility of the intended in-laws , age, occupation, wealth etc.

If all or most of the above are compatible then the horoscopes of the girl and boy are matched; and if they are compatible a date is fixed for the groom to visit the bride's home. He arrives with gifts and the pair gets an opportunity to see whether they like each other. If the pair, their parents and relatives are happy with the selection the astrologers are consulted again and dates and times for the marriage are fixed.

Traditionally the Karava's had their own service caste of Barbers called Amabtta caste. The Ambattaya caste served only the Karavas. They were attached by bonds of service and their ancestors had arrived from India with the retinue of the Karavas. The Ambattayas were the village Barbers and Physicians. Their wives were the midwives. At Karava weddings the Ambattaya ceremonially trimmed a few hairs of the groom's beard. At Karava funerals he followed the procession to the cemetery and sprinkled holy water on the grave. (M. D. Raghavan Professor Emeritus in Times of Ceylon 27/07/1953) In his Pictorial Survey of Ceylon, Professor Raghavan says that the Ambattaya family that served the Karava caste in Vaikal had the family name Chakrawarthige. The ancient Sri Lankan chronicle, Chulavamsa has a reference to this Kshatriya custom of first dressing of hair (CV 63:5)

The mother of the groom comes in front of him with a glass of milk as he leaves his home and the Groom sips the milk and gets blessed by the Mother.

Right: In continuation of the Karava warrior tradition, a younger brother, or male cousin of the bride greets the groom at the entrance to the bride's house and symbolically washes his feet . The groom drops a gold ring into the water basin as a gift to the brother and the groom walks over white cloth laid out for him by the family washerman. In the past Karava villages had their own service caste of washermen who washed only for the Karavas and lived in adjacent villages.

The wedding ceremony is in the Bride's home. On the day of the wedding, a younger brother/male cousin of the bride greets the groom at the entrance to the bride's house and symbolically washes the groom's feet . The groom drops a gold ring into the water basin. That's a gift to the brother. And the groom walks over white cloth laid out for him by the family washerman. In the past Karava villages had their own service caste of washermen who washed only for the Karavas and lived in adjacent villages.

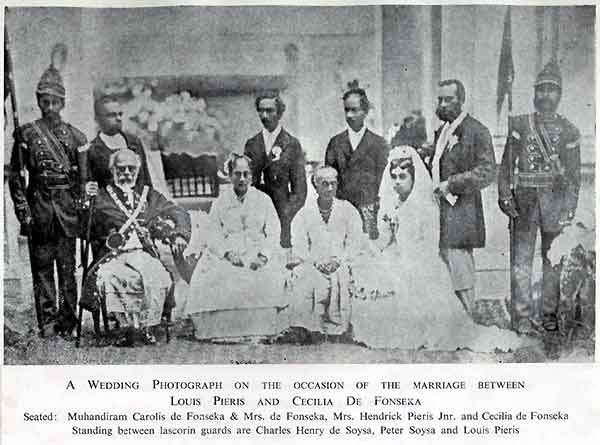

Above and below: Wedding of Loius Pieris and Cecilia de Fonseka of the Karawe community, with family and Lascorin guards. circa 1870

The bride is brought out shortly before the appointed auspicious time and amid chanting, singing and beating of drums the couple mounts the wedding dais. A maternal uncle of the bride dons a head cloth as a turban and symbolically unites the couple by tying their right thumbs together with a gold thread. The union is consecrated by pouring water from a decorative spouted vessel or chank onto the fingers. This symbolizes the kshatriya tradition of pouring holy water from the Ganges

Whilst still on the bridal dais the couple exchange gold rings and the groom adorns the bride with a gold necklace. He also symbolically drapes her with the wedding Saree brought by him and a white cloth. The white cloth is to be laid on the bridal bed and is examined by the groom's relatives the next morning for evidence of virginity.

Gifts are given by the couple to both sets of parents and grandparents. The Bride's mother is traditionally given a full roll of white cloth together with other gifts. Betel leaves, paddy and a gold coin is dropped onto the floor of the dais. These are for the family washerman.

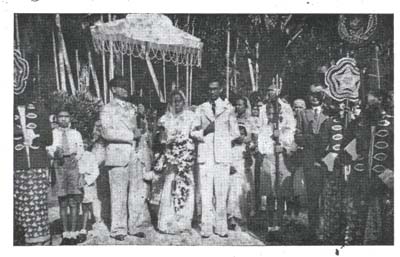

Karava weddings with traditional royal insignia. Above from the early 20th century and below from the late 20th century.

At the appointed auspicious time the bride's maternal uncle leads the couple down from the dais to light a lamp which is a custom distantly related to the ancient holy fire ceremony. As the couple is stepping off the dais to the sound of conches, drumming, chanting and singing the washerman brings down a traditional axe onto a coconut placed on the floor and expertly splits it into two halves. If both halves fall face up and with water in them it is considered a good omen for a successful marriage.

The bride wears a Siri-bo -male ( a gold necklace with seven strands worn only by the Karava brides and former queens of Sri Lanka) possibly signifying the connection to the Siri Sangabo royal line of Sri Lanka. See timeline of Karava kings

Two examples of gold "Siri bo Maala" worn only by Karava brides and former queens of Sri Lanka

Karava royal insignia, jewelry and other valuables that are being given as dowry to the bride are displayed at the ceremony.

The Portuguese historian Father Manuel Barrados writes as follows about a Karava weeding he witnessed in 1613 in Moratuwa.

"The wedded pair come walking on white cloths, with which the ground is successively carpeted, and are covered above with others of the same kind, which the nearest relatives hold in their extended hands after the fashion of a canopy. The symbols that they carry are white discs, and candles lighted in the day-time, and certain shells which they keep playing on in place of bag-pipes. All these are Royal Symbols which the former kings conceded to this race of people, that being strangers they should inhabit the coasts of Ceilao, and none but they or those to whom they give leave can use them. …, what causes wonder in this and in other people of this kind, is, that although so wretched, miserable, and poor, they have so many points of honour, that they would rather die than go contrary to it." (Monthly Literary Register 4, 1896 page 134

A southern Karava wedding as seen by a western artist in 1885. Note white canopy and foot cloth of royalty. Click image to zoom

Kshatriya Maha Sabha, Sri Lanka